year: 2021

published by: superland.space (web magazine)link: https://www.superland.space/index.php?page=article&id=5

I took a field trip to Belgrade with the intention of visiting and documenting one specific urban neighbourhood called Ada Međica, which is located on an island in the Sava River. The island is home to a site-specific community characterised by collective power, self-government, self-built solidarity, good neighbourly relations, and shared common interests.

In what way does the self-sustained community build its common language and establish its own rules? What are the residents’ common interests and motivations? What keeps them together? What is the significance of the island's informal urbanism for the inhabitants and environment?

Through analogue documentation and listening to these spatial practices, I believe we can spark a debate about our right to the city and our right to the land(scape). It is important to recognise and acknowledge community-based self-organisation as an influential part of how land areas develop and as a good contributor of citizen involvement to urban spatial planning.

This essay contains my diary notes from the field trip, records of conversations with inhabitants and members of the self-sufficient community, speculations, and personal impressions, with the intention of (re)discovering the identity of the island and the significance of informal urbanism for the inhabitants and environment.

Friday,

09:30.

I’m waiting at the Zeleni Venac bus station in Belgrade. A

bus finally arrives headed for the neighbourhood of New Belgrade,

Block 443.

In the background noise of the bus, I hear the romantic song ‘When

I Fall in Love’ (by Michael Bublé). While listening to the song, I

gaze out the window, noticing how the light reflects off of the glass

façade of the new Belgrade Waterfront development. It looks like an

real-estate advertisement for this new development. In the distance,

I can see a piece of wilderness rising above the river Sava. It is

the island Ada Međica. As we approach the final station, the bus

empties. It looks like people aren't going to the island. It‘s

sunny, I’m at the riverbank already, waiting for the boat to the

island.

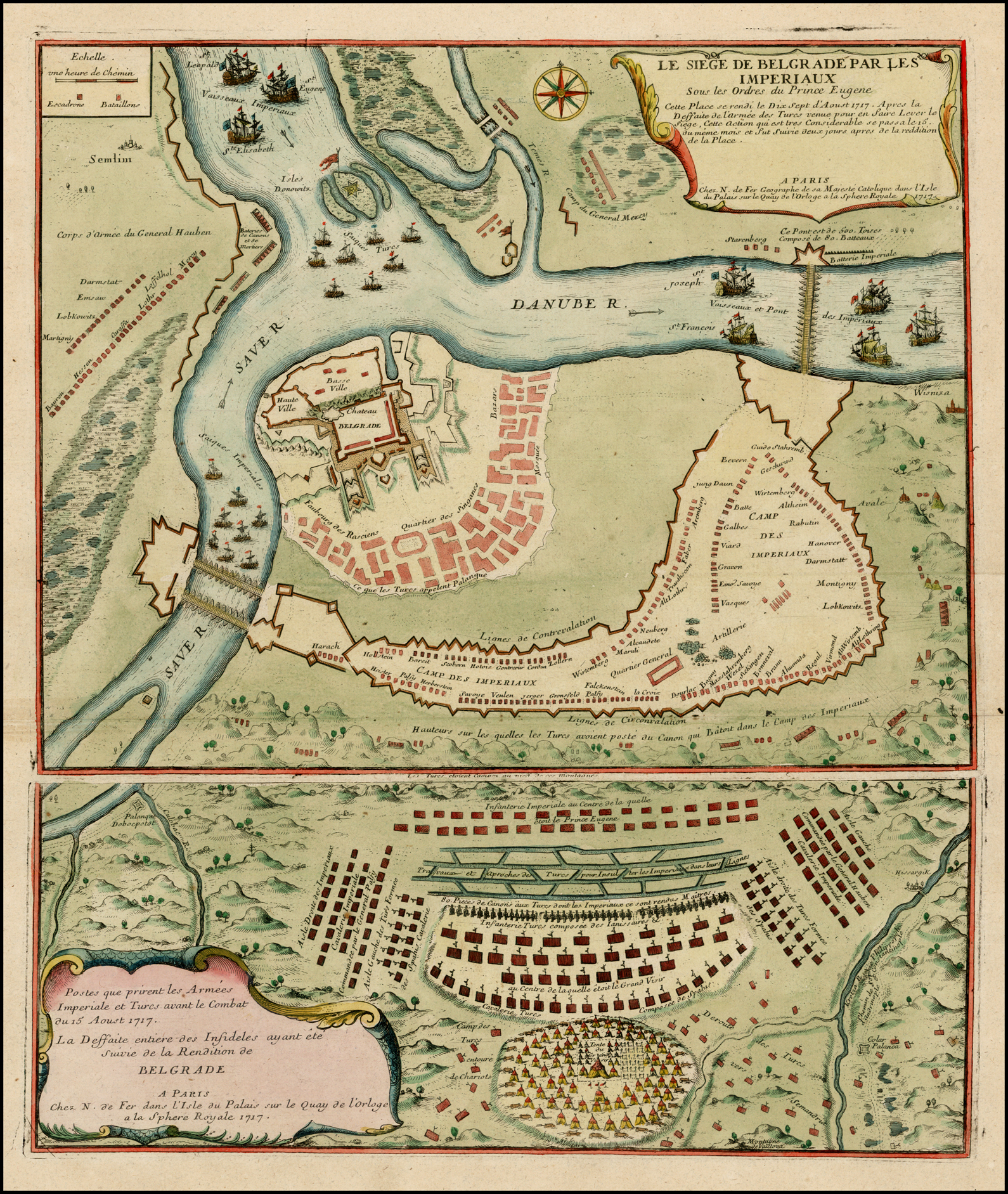

map of Belgrade 1717 (from archive)

Belgrade lies at the confluence of two rivers, the Sava and the Danube, at the point where the Šumadija Highlands and the Pannonian Plain meet. The riverbanks of the Sava and the Danube are characterised as natural ecological reserves, floodplains, recreation areas, or as the remains of former industry. What is distinct about the riverbanks, especially along the Sava, is that these areas are border zones where ‘center and periphery overlap, creating a paradoxical context in which a geographical center functions like a periphery’. It is a result of the urban planning of New Belgrade, which was supposed to be the capital of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and is located on the other side of the Sava River. In short, New Belgrade was constructed on drained marshland as a part of the socialist movement, and it was connected to the old city of Belgrade by bridges and elevated roadways. ‘When the marshland was drained, the riverside area became narrower, and though it occupied the geographical center of this new, bipolar urban structure, nothing changed in terms of the riverside’s function as a border zone’5. My first encounter with the riverbank on the Sava was characterised by a feeling of being on the outskirts of the city even though I was geographically in the centre.

Friday,

10:30.

Above me, tall willows, acacias, oaks, and birches flutter.

The cries of magpies and seagulls can be heard in the distance.

Suddenly, I feel like I’m somewhere in the wilderness, far from the

city. Through the dense trees, I arrive at the southern tip of the

island, from which I finally see the city. I feel the soft sand

beneath me. In the distance, I can see the silhouettes of Belgrade’s

developments, abandoned industry, bridges, and the concrete apartment

blocks of New Belgrade. I feel like Belgrade has forgotten its

riverbanks. The city rises on the other side of the river. The island

is left to itself.

One specific urban form located on the Sava River, in Belgrade’s municipality of New Belgrade and Čukarica, is the island of Ada Međica, an island that associates ecology with recreation, war memory, dwelling, and community rituals. As the root of its name ‘međa’ (a Serbian word for a border) suggests, Ada Međica was historically a borderland of many different states (the Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire, the Kingdom of Hungary, Serbia, the Ottoman Empire, etc.) and a site of military conflicts. The island was a weed of urban wilderness in the city until the 1960s when it became the site of the self-governing community ‘Ljubitelji Save i Dunava’ (the Society of the Sava and Danube Devotees). Through a decision of the Supreme Court of Yugoslavia, the municipal government has entrusted the community to manage and use the land of the island for a period of 99 years, without the right to sell the land. For a short time, the concept of self-governance was strongly embedded in the socio-economic policy of Yugoslavia. It was a response to both Western capitalism and the Soviet model of communism, emphasising social rather than state ownership of the means of production. Accordingly, in the 1970s, the main model for managing the entire society was based on the people’s right to self-determine.

However, it raises a question: after the failure of Yugoslavia, what happened to this kind of self-sustained spatial practice in a post-socialist city such as Belgrade? Is such a practice finished, or is it still in transition?

Friday,

12:30.

I decide to go to the other tip of the island. As I am

walking, the island’s specific weekend houses on stilts appeared

through the trees. Ada Međica is subject to frequent flooding by the

Sava, and therefore the dwellings and living conditions on the island

have been adapted to the environment of the wetland. There are about

90 stilt houses and about 300 floating houseboats on the island.

The ground floor of these weekend houses comprises an open space, hemmed in by pillars, usually containing an open kitchen with a fireplace, a dining table, and small storage area. In some houses, the ground floor is a studio for artists. From the ground floor, there are always stairs leading up to the first floor with an open veranda and one or two living areas, such as a bedroom and a living room. The ground floor is the most domesticated space of the inhabitants’ daily lives for the performance of different activities. From cooking, to feasting, to meetings, to performing, the open space is a stage for rituals, connecting the residents’ public and private lives with the land and surroundings. This open form supports the community’s neighbourly relations.

During floods, the island is regularly covered with mud and usually flooded so much that boats have to be used for transportation from one stilt house to another. When it comes to this rare situation, a veranda or a houseboat takes over as the main space for community life. What is interesting is that these weekend houses have no electricity, water, or sewage system. They use solar panels as an alternative energy source, public fountains as their main water source, latrines as toilets, and fireplaces for heating and cooking.

With self-established guidelines, self-built common interests, and methods for caring for each other, the community functions without public infrastructure. By paying annually for their membership, the members of such a community not only support and maintain their self-established network but also improve their living conditions on the island. It seems that the community’s interest is to be conscious of the environment. But I think they are more like modern hermits, familiar with the conditions and limits of the land. The Sava River and the nature of the island determine their rhythm of life and influence their thoughts and feelings.

Friday, 13:30.

As I am wandering the territory, I notice various fountains by the road, open gathering areas, fireplaces, deck chairs, and small playgrounds for children. At the veranda of one house, I hear two women drinking coffee and talking. On the ground floor, beans are cooking – a black, iron pot hung over the fire, the escaping steam gently rattling its slightly open lid.

On the other side of the island, not far from this house, I noticed a cat sitting on a staircase. I came to pet her. At that moment, her owner appeared and invited me to his house to try his ‘rakija’, a fruit brandy made from his white roses.

“I don’t know where to start. There are so many stories related to this island. The first settler on the island and the person who started all of this was my dear friend, the architect Ph.D. Predrag Ristić. He built the first tree house. He often stayed on the island in search for inspiration for his work, away from the city centre. This was in the 1960s, when the communists demolished his tree house three times because it was a gathering place for young people whose behaviour and dress code did not match the character of Tito’s Youth. But every time, Peđa protested and rebuilt the house again, in different forms, from the materials which he would find around. Some of his houses are still standing here at Ada Međica. Let me show you some of the sketches, drawings, and old pictures I got from him. I would also like to give you the book I wrote “Razgovor s biljkama” (A conversation with plants). In the book, I wrote how people can learn from plants, how trees can heal and help us feel complete peace. Some of the therapy sessions with the plants, the healing, I did it with a group of people here, at the island. The island is an oasis.”

In the 1960s, after several consecutive demolitions of his houses, the architect, university professor Predrag Ristić decided to fight for his right to be on the river. As I wrote at the beginning of this essay, in former Yugoslavia at that time, self-governance was an important goal of the socio-economic policy, which emphasised social ownership in urban policy. Therefore, the architect used this motive and, together with his friends, also lovers of the river and nature, founded the autonomous community Society of the Sava and Danube Devotees. The municipal government gave them the right to manage and use the island.

In 1965, a dispute against this community which lasted for 20 years began. After the first weekend houses on stilts appeared in Ada Međica, the city’s authorities filed a lawsuit against the self-sustained community via public enterprise because they feared that the island would become privatised. However, the interests and motivations of this informal autonomous organisation were much more grounded than the authorities’ fear of having land privatised. After 20 years of struggle, the community of the Sava and Danube Devotees won the case, and the Supreme Court of Yugoslavia gave them the right to manage the land for 99 years.

There are many social rituals in this community. Every year, members of the community organise a swimming marathon around the island. Once, in 2016, during the marathon, a heavy, unexploded bomb from World War II was discovered near the tip of the island. The bomb was removed and destroyed, but it reminded everyone that the island was once the site of military conflicts.

![]()

Friday,

15:30.

What fascinates me is to feel the freedom of wandering around

this neighbourhood with no fenced-in plots of land. You have the

chance to come into direct contact with the inhabitants, have a

coffee or lunch in some of the weekend houses, and explore the

landscape of the island.

Finally, I reached the northern tip of the island, where there is a restaurant and some gathering areas for visitors. The island’s tip is concreted to prevent erosion by the river’s flow. The flow of the Sava is so strong that it pushes the island downstream 50 to 100 centimetres per year. The fortification concreted wall was made by the city authorities, and it represents the only cooperative project with the city’s government.

It left me wondering: from being a land of military conflicts, to a wild oasis of nature, to the settlement of a self-sufficient community, what will happen to Ada Međica in the future, after the community’s right to manage the land expires? Will the island become the privatised property of this informal community? Or will it slowly float downstream to the Ada bridge10? Or will the island become a new potential recreational development site for the city? I hope that this site-specific case can show how important it is to actively engage citizens to be part of urban planning.

from the field diary